Why and how to use pen and paper

Designing algorithms with no code

MiguelMJ -It’s a common thing to see programming students staring silently at their code editor, with a blank look in their eyes, not knowing where to start when they are given an assignment. Although most teachers say “pick up pen and paper before programming”, there is a reason why some just don’t do it: mostly because they don’t know why or how.

So, how important is to “pick up pen and paper”?

Your coding skills will always be limited by your problem solving skills

Programming is, by definition, designing a solution. In most cases this means designing an algorithm (sorry, declarative programming).

To be a great programmer, it is more important to develop your ability to solve problems algorithmically and think abstractly about data than to know perfectly the syntax of any language. It will let you deconstruct the problem and solve it with whatever tools you have.

How does it help using pen and paper?

In pseudocode, a flowchart or a drawing, data need no type, there are no syntax errors and you can focus on what you have and what you want, with the level of abstraction you need.

Our minds understand visual information better

With code, it happens like with mathematical language. Our brain knows how to interpret images almost directly, but needs some more resources to interpret code or math.

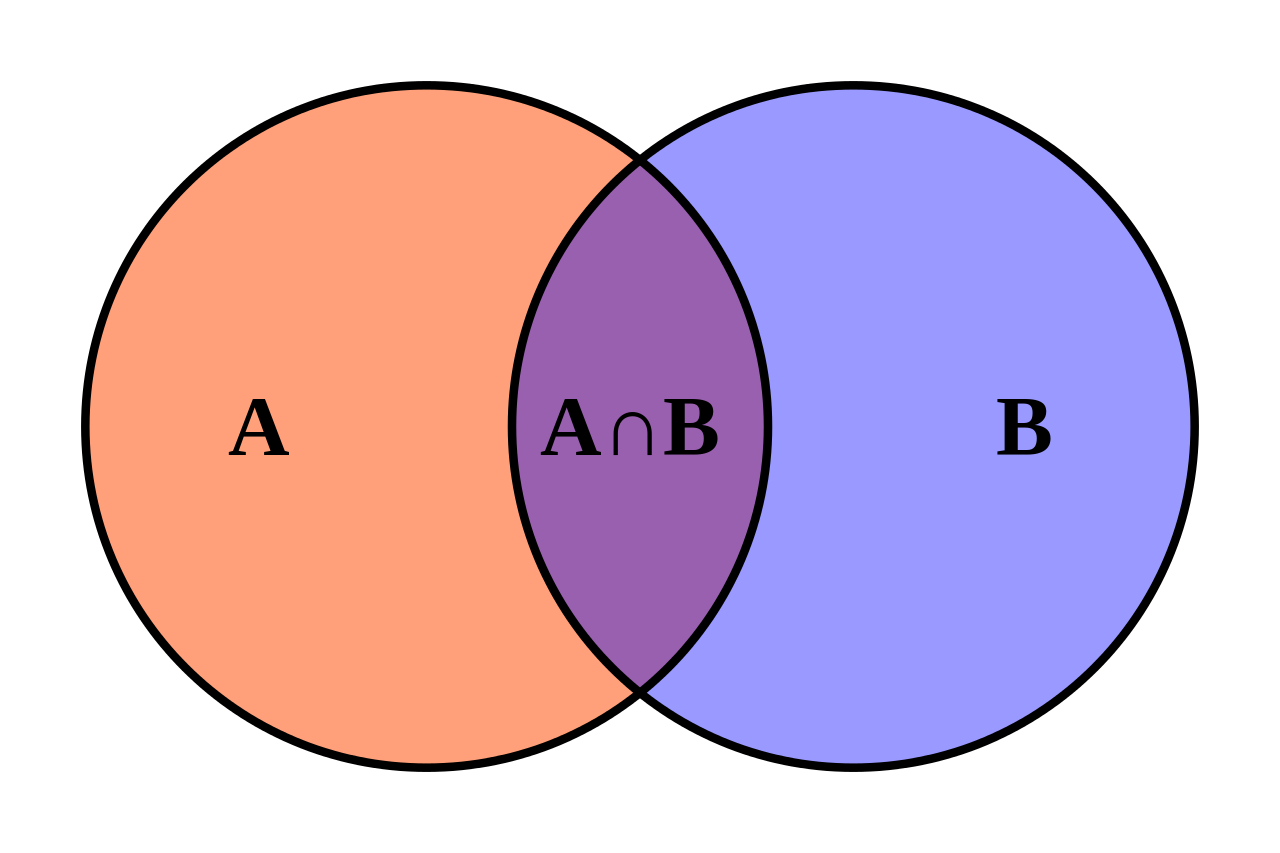

Intersection of two sets

| Math | Image |

|---|---|

Source: Wikimedia Source: Wikimedia |

The process your mind takes to understand the image is much shorter than to understand the expression.

That applies to programming too

-

The same happens when actively creating something. It’s easier for you to come up with a solution while using your eyes and hands on the paper than directly trying to express it in code.

-

Furthermore, when you design before writing, you can debug more easily. The design offers you a panoramic view of the algorithm, which you can contrast with the code in successive iterations, to recognize the nature of the error.

If you’re already convinced to pick up that pen and paper, you might find useful some tips for the process.

Some guidelines on how to think when designing an algorithm

There are several ways to do this. In fact, Software Engineering offers a lot of different models on how to design software and abstract architectures to approach a lot of different problems. Here I want to give a very generic method, on which almost any other process is based.

Thinking on the data representation

-

What information do you have and how you want/need to represent it? Are you going to use predefined types or structures of the language? Do you need to define your own?

- Draw some examples of the data and let your brain perceive the gaps or redundancies.

-

What are the basic operations you can perform on this information? You should be clear on what transformations you can apply to your data.

-

In many languages the most basic is asignation. Be sure to understand how it works. The rest usually depends on whether it is a number, a string, a collection, an object, etc

-

You will be able to use these basic operations as the building blocks of your algorithm.

-

Thinking on the process

These are not sequential steps, but separate advice to develop your solutions.

-

Before even trying to define the algorithm, it is better to have some examples of input and output. For this you can also specify some preconditions and postconditions: What is true before the algorithm is executed? What must be true after the algorithm is executed?

- If the algorithm depends on some arguments, pay special attention to them. Also, what useful information can you extract from them? Write that down too, if you think it will be worhtwhile.

-

You don’t need to think it straight from the first to the last step. Sometimes the last part of the algorithm is clearer than the first one. Go ahead and specify its latter part, and then focus on how to get to that point.

- Write or draw the steps you see clearly, try to connect them and fill the missing steps to finish.

-

Divide the problem into subproblems until you are able to solve them with your basic operations. You can write first a high-level pseudocode or flow-chart version of the solution, and then go through each step, decomposing it into more steps.

- If you think you have more than one option, you can even specify various solutions and try them in code, to see if one works better than another.

Conclusion

Different minds deal better with different methods, but in the end, learning and practising are the two only ways to improve.

There is a direct synergy between solving problems and programming, but always remember: the solution can exist without the code; the code can’t exist without the solution.